After leaving university and completing the obligatory post-doctoral sojourn the priority was to find gainful employment. Completing several unsuccessful interviews with pharma companies (who shall remain nameless). I got a job offer, which I accepted, at the Central Research Laboratories of a Swiss based pharma/agro/industrial chemical company.

The site was on the industrial estate of Trafford park in Manchester, UK. At that time quite a dilapidated piece of real estate. The central research facility occupied the third floor of the building on the industrial chemicals division site of the company. I approached the place with some trepidation and was delivered to the personnel department by the man at the gate. After the usual lectures by them I finally went up to the labs where I was introduced to everyone, seemed a great bunch of blokes, and got settled into my new office.

My office-mate was an Irishman who studied at Manchester University, an odd-ball of a sort, as it turned out. My lab-assistant was a local lad and very experienced. There were three large labs on one side of the a corridor with offices opposite, I was given a place in the second lab and there were 2 chemists and their teams in each lab. So quite a bit of space. I got busy with my first project.

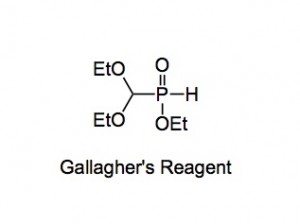

The field of chemistry done there was organophosphorus chemistry where our management studied what the rest of the company were doing and came back and said we should make compound x, y or z as a phosphorus analogue. Now it wasn’t phosphonates we were making but phosphinates. They had come up with a useful reagent, affectionally called Gallagher’s Reagent (GR), named after the chemist who first published it’s preparation and use in the Australian Journal of chemistry.

This compound could place phosphorus, at that oxidation level anywhere, even at multiple sites in a given target structure. This was the justification for one’s existence within the company. “Make phosphinates, analogues of your best compounds, they are bound to have better biological activity or rust prevention properties than ANYTHING you have ever seen thus far in your exploration of science”. Large claim. Which was actually true to a certain extent.

This compound could place phosphorus, at that oxidation level anywhere, even at multiple sites in a given target structure. This was the justification for one’s existence within the company. “Make phosphinates, analogues of your best compounds, they are bound to have better biological activity or rust prevention properties than ANYTHING you have ever seen thus far in your exploration of science”. Large claim. Which was actually true to a certain extent.

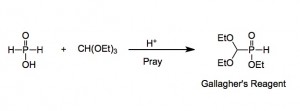

Now this GR was truly great stuff, it was (is) made from the reaction of anhydrous hypophosphorus acid, triethylorthoformate and a smidgeon of acid

Now note the word pray below the arrow, not a new reagent, depending upon your point of view, I suppose, but necessary. The synthesis started from 50% aqueous hypophosphorus acid, quite innocuous stuff. BUT it has to be almost water free for this reaction to work efficiently. Now we pumped it down to dryness upon which it crystallised. This is funny stuff, this compound. We routinely did this to give 10kg of the acid and pumping down 20kg of the solution took time and some decomposition. I was watching them do this and noticed a rather bad smell. I was about to comment when the technician opened a tap on the top of a trap, the smell became immediately more intense and a 6 foot long flame shot out of the top of the trap. The smell was replaced by a more recognisable one and I went home to change amongst peals of laughter. That was my first “exposure” to some sort of phosphine.

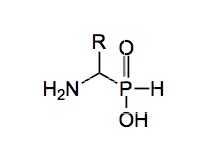

After the reaction the product was distilled in the molecular still and appeared as a clear oil, along with more phosphines trapped in the traps. But I was wiser and knew what was going to happen but I was disappointed this time, they just added bleach and I didn’t get my flame. The GR was reasonably stable, after a few weeks an orange precipitate formed, which if you removed by filtration burst into flames accompanied by another more virulent smell than that produced during its preparation. Years later I met Phospho-Meier, an organophosphosus expert who the company had poached from another company for loads of money to make better glyphosate. A task he did not complete, but he managed to publish “The Chemistry of Phosphorus part 649” during his time with my company (he retired before part 650 was finished). Anyway I asked him what this orange stuff was, he didn’t know, but launched into a discourse lasting about an hour, telling me exactly nothing. To this day I don’t know what it is but know not to remove it. Moving on, GR reacts with a variety of functional groups, imines, aldehydes, ketones and the like. In fact they had made all the phosphinate analogues of the natural alpha-amino acids.

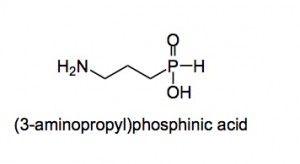

They also started on the other amino acids, GABA was of particular interest as the Pharma division had a large CNS program running to find novel agonists and antagonists of this neurotransmitter system. The hit agonist was gamma-aminopropylphosphinic acid.

More about this later as well as the adventures with the GR and the management!

1,975 total views, 1 views today